It’s a two-hour drive from Hazel Dell to The Dalles, but a high school boy running late for a baseball game can do it in an hour, forty-five.

Don’t ask me how I know.

To get there, you’ll spend most of your time meandering east, through the silt and sandstone strata of the Columbia River Gorge, on Oregon’s Interstate-84. It is a stunning landscape, one consumed ravenously by sightseers and photographers and unsuspecting travelers who marvel at the evergreens, the waterfalls, and the moodiness of the great Columbia River.

This freeway will take you to Utah, if you let it, past the satanic stench of rotting cow dung at dairy farms east of Boise, to the spiritual high ground of Salt Lake City, or thereabouts. I nearly made this mistake once. Made it as far as Twin Falls, Idaho, where I watched a junior college all-star game and took a pass on an outfielder from North Idaho College. Jason Bay went to Gonzaga instead where he hit thirty-five home runs the next two years before signing with the Pittsburg Pirates and being named National League Rookie of the Year in 2004. That memory tastes like biting on an aspirin tablet and washing it down with a kerosene highball.

To get the tastier memories from this interminable stretch of asphalt—the ones seasoned with fresh herbs, a hint of cayenne, and roasted to honey-sweet perfection—my mind veers off at Exit 85, as many miles east of Portland, Oregon, and winds its way up Brewery Grade to the corner of 12th and Oregon Street. Here, Quinton Street Park’s tired facade stands like the hole-in-the-wall cantinas my buddy Ryan Brust likes to take me—places I would drive right by and in the process forego some of the best meals I’ve ever eaten. Built asymmetrically as the Vietnam War was getting underway, its paint is peeling and the red plastic seats behind home plate have faded.

I came to Quinton Street Park as a visitor from Vancouver for the first time in the summer of 1982, one of three high school sophomores riding the bench on a summer team chock full of older, better players. We’d come to play a night game against the Columbia Gorge Hustlers, a formidable American Legion team that a few years earlier had produced major leaguers Ken Daley and Jeff Lahti. My teammate, Bruce Barnum, newly graduated and days away from reporting to football practice at Eastern Washington University, told me not to move after he was called on to pinch-hit late in the game. It would be his final at-bat, a curtain call in a sport he was giving up forever in favor of one that has paid his bills ever since, most recently while serving as head coach at Portland State University. He grabbed a bat, spat a mouth full of Red Man between my shoes, deadpan, and fighting for air through a nose jammed with hay fever, said, “Just sit there and shut up, meat. You don’t want to miss this.”

Barney had always scared the hell out of me. He was two years older, seventy pounds heavier, and had worn a full beard since he was fifteen. His big and muscular frame moved through the world at a glacial pace, unless, of course, he was pursuing a running back coming across the scrimmage line. If you saw him on the gridiron, you knew he had another gear to go to. When he spoke, I listened.

We had arrived three hours earlier in a half-dozen old sedans, pickup trucks, and our coach’s silver Toyota Celica liftback. Through open windows, a mix of Van Halen and Merle Haggard songs blared from cassette decks, the sound mingling with the dust cloud we created driving through the gravel parking lot.

The July sun was relentless. By game time, it was still over a hundred degrees. The Hustlers’ coach, Doug Sawyer, watered the dirt with a garden hose while barking orders to his players, but by the time he made his way to first base the left side of the infield was already dry. Things felt heavy and people in the stands moved around slowly. Not even the smell of onions and hamburgers cooking on the grill was enough to get them to leave their seats. They’d wait, as they always did, for the sun to descend below the bleachers while the third baseman shaded the blinding light with his bare hand and prayed for left-handed hitters who could pull the ball. In this sweltering hotbox, folks had simply lost their will. But when the darkness took over, cooling the air and drying the sweat from the collar, the concession stand came to life.

And then Bruce Barnum was announced.

“Bar-ney! Bar-ney! Bar-ney!”

The chant began slowly, organically, in our dugout before spreading to a small group of parents seated in the bleachers above. Soon strangers joined in and Quinton Street sounded like I imagined Yankee Stadium did when Reggie Jackson came to bat with the game on the line. Barney stepped into the batter’s box, smirking, soaking up the moment and laughing toward the dugout. He spat in the catcher’s direction, waggled his bat, and waited for a pitch from a kid who looked baffled by the sudden turn of the crowd.

With a mammoth swing—one best suited for a backyard Whiffle Ball game—Barney launched a towering fly ball that sailed well above the light standards and disappeared into the night sky. “Dammit!" screamed the pitcher as he ran to back up home plate.

Had Barney just called his shot? Had he really just capped his baseball career with a home run to left field at Quinton Street?

My teammates and I stood and held our breath as the left fielder sprinted to the warning track and prepared to jump. He found the fence with his hand—Hustlers were nothing if not well-coached—then reversed course, letting the ball fall gently into his glove ten feet in front of the outfield fence. The dugout exhaled and just like that, the baseball career of one of my favorite and most intimidating teammates was over. It was the most dramatic can of corn I’ve ever seen.

And Barney couldn’t have cared less.

It looks the same to me, Quinton Street Park, although former Hustler Mark Beaton says the press box, high atop the home plate bleachers, is new. Then again, he has lived in Michigan for thirty years and his memory can be best described as faulty, distorted, and unreliable.

In 1983, a year before we became college teammates and I began counting him as one of my closest friends, I got two hits off Mark—the only ones he surrendered—in a game he pitched against the Vancouver Cardinals under the lights at Quinton Street. He will tell you that the first hit would have been a perfect drag bunt—one that stopped on the third base line twenty feet from home plate—had I not taken a full swing on a changeup and scuffed the ball off the end of the bat. He will then tell you that the second one was a seventeen-hop jam shot that narrowly escaped the reach of the second baseman, a ball hit so feebly that it came to rest, on its own, six feet into the outfield grass. I have argued for more than three decades that both were line drives that launched off of my bat like an F-14 Tomcat. But I digress. My point is, while a steady drip of McNaughton’s has done little to dull the pain and humiliation from which my dear friend suffers, I think Mark is right about the press box.

At field level, the original press box was far less conspicuous than its replacement—directly behind home plate, yes, but buried under the bleachers like a bad report card. It was clearly an add-on, a four-by-twelve wooden box with a door on one end, framed out toward the field from the block wall stadium. Before games, a horizontal sheet of plywood, hinged at the top, was swung upward and attached with rusty carabineers to the ceiling joists, giving personnel a view from behind home plate. On both sides of the bump-out, loyal Hustlers fans in folding lawn chairs lined up side-by-side along the block wall, protected from play by a chain link backstop in front of them, and from the blast-furnace heat by the shade of the overhanging bleacher deck.

To be sure, these were the best seats in the house, claimed early each gameday by flabby-armed grandmothers wearing cool summer smocks, and their men in Romeos, short-sleeved blends, suspenders, and a belt—just in case. Unless they got up for a cup of black coffee, they stayed put in their lawn chairs, occasionally reminiscing about Daley and Lahti, or Dale Murphy and Jacoby Ellsbury, or any number of great players that they watched play at Quinton Street Park. Thanks to Coach Bob Brockman, who hosted the annual Oregon State-Metro All-Star Series at Quinton Street Park for decades, every great high school player in the state had played here at least once. As head coach recruiting for my alma mater, the University of Portland, I enjoyed eavesdropping on this generation and hearing their stories of Hustlers who eventually became college teammates with whom I shared a locker room, including Beaton, Larry Melton, and Dean Dollarhide.

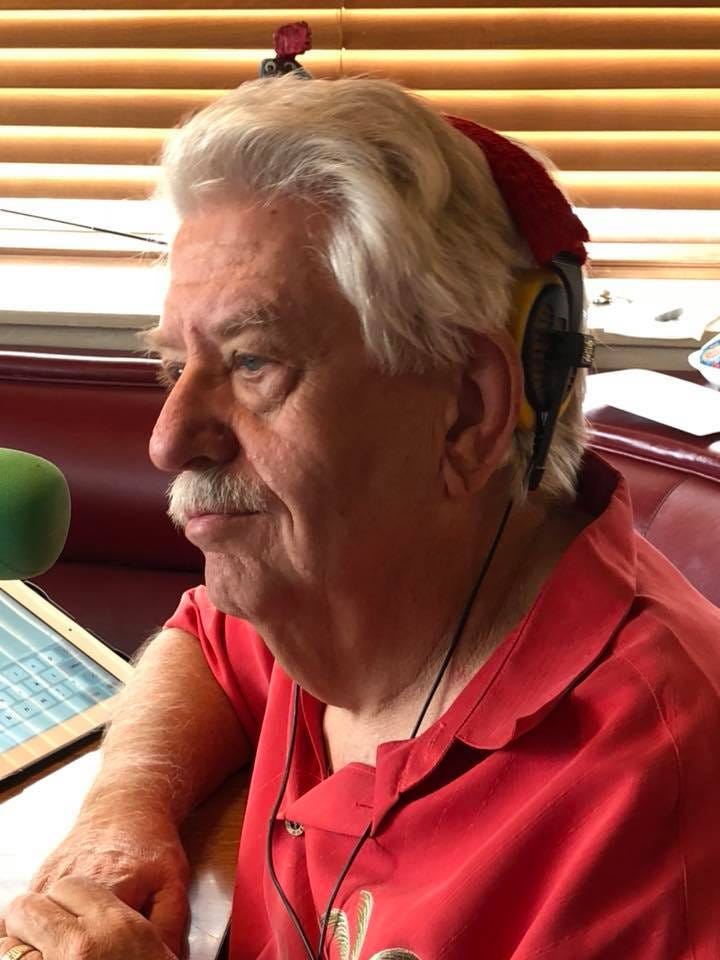

Al Wynn sat in that old press box more times than he cares to count. He’s been doing it since 1974. Nearly eighty, he still hosts a weekly radio program he runs remotely from a sticky booth reserved for him at Cousins’ Restaurant and Saloon—something he’s done nearly 11,000 times now. At Quinton Street Park, he and the folks in lawn chairs call each other by name.

Baseball, in small towns like The Dalles, is made special today thanks to folks who rest their backs against stadium walls and radio broadcasters who have coffee with the catcher’s grandpa. They are volunteers who pay full freight for a ticket to the game, then insist on manning the grill. They are simple folks that know the pain of war and the uncertainty of economic hard times. They are people who enjoy watching the Petersons’ grandson play just as much as they did their own, twenty years earlier.

In 1956, a group of them drove their pickups and flatbeds to Portland’s Slabtown neighborhood when the news of Vaughn Street Park’s razing reached home. They returned with old irrigation pipes, framing lumber, bleacher seats—anything they could get their hands on—that had been part of Oregon’s most historic ballpark. Then they set about building one of their own using parts forged when Bill McKinnley was carving his initials in the Resolute Desk. Now, more than 120 years old, some of those materials remain a part of Quinton Street Park today. In fact, it is virtually guaranteed that if you watched a game here before 2010, roughly when the bleachers were replaced, you splintered your behind on the same wood on which Portlanders sat and screamed the names of DiMaggio and Paige and Williams.

Some years ago, I decided that I was not destined for baseball riches. Try as I might, I would never call home the lavish, multi-million dollar stadiums that featured viewing decks for wine-swilling VIPs and carpeting embellished with the school mascot in the middle of locker rooms full of Xbox machines. These facilities were born out of an arms race in college athletics in which I received neither a number on a bib nor one written on my salt-stained skin with a black grease pen. I have always been a guest in such quarters, oohing and awing like the rest of the riffraff at the artwork hanging on the walls. Sometimes I departed after the owners had treated my teams like unwanted strangers, other times after making off with the good china. Either way, I never felt welcome.

Quinton Street Park lacks the pretentiousness of its palatial counterparts, so much so that the stadium isn’t even on Quinton Street, but rather at the corner of Oregon and 12th. Like a bashful child hiding in the back of the classroom, Quinton Street sits quietly beyond the left field fence, gaining notice, only briefly, when a right-handed hitter pulls one out of the house.

Don’t get me wrong, with its ample seating, lights, a concession stand, home and visitor locker rooms, and a batting cage, Quinton Street Park has amenities that most high schools across the country—and every college program I started out working in—could only dream about. For most of us, getting to play a game here as a kid was like getting to play at Dodger Stadium.

But unlike its showy counterparts, this place was not built from the deep pockets of a wealthy alum or a businessman who drives a German sports car, lives remotely, and expects to see his name on the scoreboard when he comes to town for board meetings. Instead, Quinton Street Park exists today thanks to the community that surrounds it: the school district that owns the land and leases it back to local programs; the coaches who oversee those programs, as well as the daily maintenance of the baseball field; the Hustlers players and parents who clean and paint and pound nails when needed, propping the place back up when its knees get weak, smoothing its wrinkles when the sun damages its skin; and a foregone generation of townfolk who hauled the place from Portland and rebuilt it for a community that has loved it for nearly 70 years.

The Dalles does not have professional sports, no Topgolf, and no opera house that I’m aware of. When folks here want a night out in the summer, some of them still go to Quinton Street Park, where they can sit against the stadium wall that they—or people they knew—helped build.

And where the white-haired man in the press box not only announces the starting lineup, he also owns the radio station.

Thanks for reading, Rich. I'd like to think the same.

These old baseball stadiums (TOBS) harken us back to the days when we played ball and had dreams (outlandish as they were) of the "Big Show." I well remember Vaughn Street Park, home of the Portland Beavers of the Pacific Coast League. Hot dogs never tasted better than at the Vaughn! I attended many Beavers games there in the 1940's while living with my aunt & uncle in Newberg, OR. TOBS have the personalities and history of the local inhabitants that are often times much more interesting than those of the impersonal Big League stadiums. By the way, as you so well know, a slow dribbler through the infield is only remembered in the box score as a HIT, and no historian, or some other person not at that game and later reviewing the records can remember it as anything but a HIT!